Amazon and MGM: Time Is A Flat Circle

The New Chapter Is The Same As The Old Chapters

Seven Stories

There are famously only seven plots in all of Hollywood

Overcoming the monster

Rags to riches

The quest

Voyage and return

Comedy

Tragedy

Rebirth

The twisted tale I am about to tell you has all seven plots in one story. It is the 97 year history of MGM, once the king of the jungle, Leo the Lion, now only worth $8.45 billion to a retail company. Along the way, many fortunes were gained and lost, there was comedy, tragedy and rebirth. Lots of rebirth.

Amazon and MGM today announced that they have entered into a definitive merger agreement under which Amazon will acquire MGM for a purchase price of $8.45 billion. MGM has nearly a century of filmmaking history and complements the work of Amazon Studios, which has primarily focused on producing TV show programming.

“MGM has a vast catalog with more than 4,000 films—12 Angry Men, Basic Instinct, Creed, James Bond, Legally Blonde, Moonstruck, Poltergeist, Raging Bull, Robocop, Rocky, Silence of the Lambs, Stargate, Thelma & Louise, Tomb Raider, The Magnificent Seven, The Pink Panther, The Thomas Crown Affair, and many other icons—as well as 17,000 TV shows—including Fargo, The Handmaid’s Tale, and Vikings—that have collectively won more than 180 Academy Awards and 100 Emmys,” said Mike Hopkins, Senior Vice President of Prime Video and Amazon Studios

Amazon would like you to believe they bought a century-old company with a film library stretching back to World War I. They did not. What they bought was a ghost of that company. The vast majority of films they just purchased were not produced by MGM. The biggest asset in the purchase, the James Bond franchise, came over with the United Artists merger in the 1980s.

Shall we get to it?

Act The First

Marcus Loew began life in a New York City tenement, and ended it only 57 years later in his palatial Glen Cove estate. In between, he helped invent the movie business. In 1919, Loew was already very wealthy, owning in succession vaudeville theaters, nickelodeons, and then movie theaters. As World War I came to a close, he had about 150 theaters in eastern cities, and demand was growing rapidly every month. Sounds great, right?

But he also had a problem. He had this new, growing distribution medium that was disrupting entertainment. But there were not enough films. Thomas Edison was of the opinion that he was the only person legally entitled to make motion pictures. There was a lot of production in Queens, and Edison would send thugs down to sets to rough up producers and break the cameras. Also, Edison’s films were terrible. The origin story of most of the Hollywood studios were eastern theater owners who turned to making films to fill their theaters with non-terrible movies, and then moved to Hollywood for the better light year round, and to get away from Edison. Loew’s problem was that supply was constrained by Edison and his thugs. He needed a pipeline from Hollywood.

In 1919, Loew bought one of these westward migrants, Metro Pictures. Five years later, Sam Goldwyn, another migrant from the east, lost control of his studio, and Loew bought that, too. It came with two of the Golden Age Hollywood icons: the Culver City lot, and Leo the Lion. But it did not come with Sam Goldwyn, and Loew wanted to stay in New York to run his very profitable theater chain. Louis B. Mayer had an asset-light production company with no studio or actor contracts. Loew acqui-hired Mayer for half a million dollars, the smallest of the three transactions. Together, they made Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, MGM.

MGM was born because Marcus Loew had a growing distribution channel that needed more content.

With Mayer came Irving Thalberg, the legendary head of production who became the prototype for successful Hollywood producers. Beginning with the original silent Ben Hur in 1925, MGM was the studio of biblical epics, patriotic Americana, and lavishly staged musicals. While a few months late to sound, MGM dove in head first on Technicolor, and Mayer loved a saturated palette. The peak of the MGM style can be seen in their 1939 films, Gone With the Wind, and The Wizard of Oz.

MGM owns neither of these films now. They don’t even own Dorothy’s ruby slippers, but we’ll get to that.

Things changed dramatically for all the studios with the onset of World War II. With many of their customers in Europe and the Pacific, attendance dropped. The studios had built a system with very high fixed costs: the the actor contracts and the studio itself. These were very expensive, which meant that the incentive was to make as many films as possible to spread those costs across as many releases and tickets as possible. MGM had the most contracts — “More Stars Than There Are In Heaven” was their motto — and the largest lot, and released almost a new feature film a week, along with shorts.

Mayer ended the contracts of their five most expensive contract players, all women, and halved the slate from 50 films a year to 25. They still made expensive, lavish movies, but on a smaller scale. Mayer always had is eye on keeping the brand unchanged.

But the bigger blow came in 1948 in US. v. Paramount Studios. The result was a series of consent decrees in which the studios had to divest from their theater chains, or in the case of MGM, Loews had to divest from MGM. MGM got dinged in 1952. Mayer had been fired the year before, and Loew and Thalberg were both long dead. The divestment completed in 1957.

The new MGM floundered in the 1960s, and soon their assets began to look better than the studio that owned them. Investor Kirk Kerkorian was mostly interested in the brand, which was still the pinnacle of Hollywood glamor. He bought the studio, and sold off a lot of the pieces, including part of the Culver City lot, and Dorothy’s ruby slippers. By the end of the 1970s, MGM was mostly a hotel-casino. Kirkorian split the two off in 1980.

The new entity merged with United Artists, another old, storied Hollywood name with a twisted history. Transamerica owned UA, and like many other non-media companies, had quickly tired of the film business, just as AT&T is today. At this point, MGM/UA was mostly “distribution,” which in this context means selling to the actual distributors — theaters, TV and home video. But like in 1919 when the theater business was taking off, by the mid-1980s, there was another new distribution medium that was in need of content to fill it.

Act The Second

Ted Turner began life under considerably different circumstances than Marcus Loew, but in 1985, he had the same problem as Loew had in 1919. At the time, he owned CNN and the TBS Superstation, and was planning TNT. CNN made its own 24-hour schedule, but TBS and TNT needed licensed content, and that was getting more expensive. Ted Turner had a new distribution channel that need to be filled.

In one of those Only In The 80s deals, Turner bought MGM/UA with massive leverage. But he only wanted the catalog, so he sold off the rest. The Culver City lot went to Lorimar/Telepictures, then to Sony, still its resident studio. The rump MGM/UA, along with the UA catalog, went back to Kerkorian, now the owner for the second time. Turner kept the pre-1986 MGM catalog. This also came with the pre-1950 Warner catalog, which MGM had purchased when Warner was having their consent decree troubles. That includes Bugs Bunny. Turner also got some Paramount animation, including Popeye.

Turner filled TBS and TNT with these films, and started two new networks, Turner Classics and the Cartoon Network. Turner Entertainment was born because Ted Turner had a distribution channel that needed filling.

In 1996, Time-Warner bought Turner. They got their pre-1950 catalog back, as well as the pre-1986 MGM library, which is owned now by AT&T, and soon the new Warner-Discovery company. That is who owns most of the films produced by MGM.

1986-2002 were MGM/UA’s most tumultuous years. The rump MGM/UA limped along under Kerkorian as a “distributor.” He then sold it in 1990 to Giancarlo Parretti, backed by Credit Lyonnaise. When the company went bankrupt, Credit Lyonnaise wound up with it, and sold it back to Kerkorian, now the owner for the third time.

From 1992-2002, MGM/UA was still mostly a sales organization. Kerkorian bought other small catalogs, like the pre-1996 Polygram and Orion libraries, and built it back up to about 4,000 titles. They also continued to make some films, including the Bond franchise, which came over with UA in 1981, and Kerkorian bought back from Turner in that prolonged battle.

But like in 1919 and 1985, in 2002, there was a new distribution medium that needed content to fill it.

Act The Third

Sony was not an upstart like Marcus Loew or Ted Turner, but they also had the same problem in 2002. They had a distribution channel that needed more content. Still smarting from the Betamax-VHS format war, Sony was determined not to let that repeat with the HD replacement for DVDs. They very much wanted their Blu-Ray format to be the winner this time.

Sony bought MGM/UA, but they never brought it into Sony Pictures. They just wanted to make sure those 4,000 titles were released on Blu-Ray, not HD-DVD. The good news is that Sony won the format war, in part because of those 4,000 titles. The bad news is that it didn’t matter, because physical product lost out to streaming services, like Amazon Prime.

MGM went in and out of bankruptcy in 2010, and has been puttering along since in much the same way it has since roughly 1996 when Kerkorian cobbled together those 4,000 titles.

Now in 2021, there is someone with a new distribution channel that needs more content.

Act The Fourth

Hollywood movies all have three acts, but this is a strange story, so here we are in the fourth act of this dramedy. Amazon has much the same problem that Marcus Loew, Ted Turner, and Sony had before. For many years, Amazon, Netflix and Apple have been trying to build something for video very much like Spotify or Apple Music. Everything, all the time, available in a single interface.

But the music labels went through over a decade of drought before they agreed to this arrangement, which has been very lucrative for them.

But the studios have never been interested in that sort of arrangement. They see streaming as a chance to get back what they haven’t had since the 1940s — their own distribution, and a chance to form brand identities again. Disney is the only studio with the same brand as they had a century ago.

So now Disney-ABC has Disney+. Comcast-Universal-NBC has Peacock. Warner-Discovery will have HBO Max and Discovery+. Viacom-Paramount-CBS has Paramount+. The only studio without a streaming service is Sony-Columbia, unless you count the underfunded Crackle.

Once current contracts begin to run out, there will only be one major studio out there selling their good stuff to the streamers. Licensing costs will go up, and there will not be enough on the platform to make it a compelling monthly subscription. When Warner decided to hoard Friends for HBO Max, and not re-up the license with Netflix, where it was one of their most popular shows for years, it was a warning shot that no one needed. The Netflix, Amazon and Apple pivots to original programming can be seen as directly related to this.

So just like Loew, Turner, and Sony before it, Amazon’s acquisition of MGM should be seen as a defensive move to shore up the rear flank of Prime Video. It is a backstop for a world where no one is selling the good shit. They get a hodgepodge of stuff with no real brand identity. Besides Bond, the best is the good stuff from UA, Polygram and Orion, a lot of that 1970s or 1980s vintage.

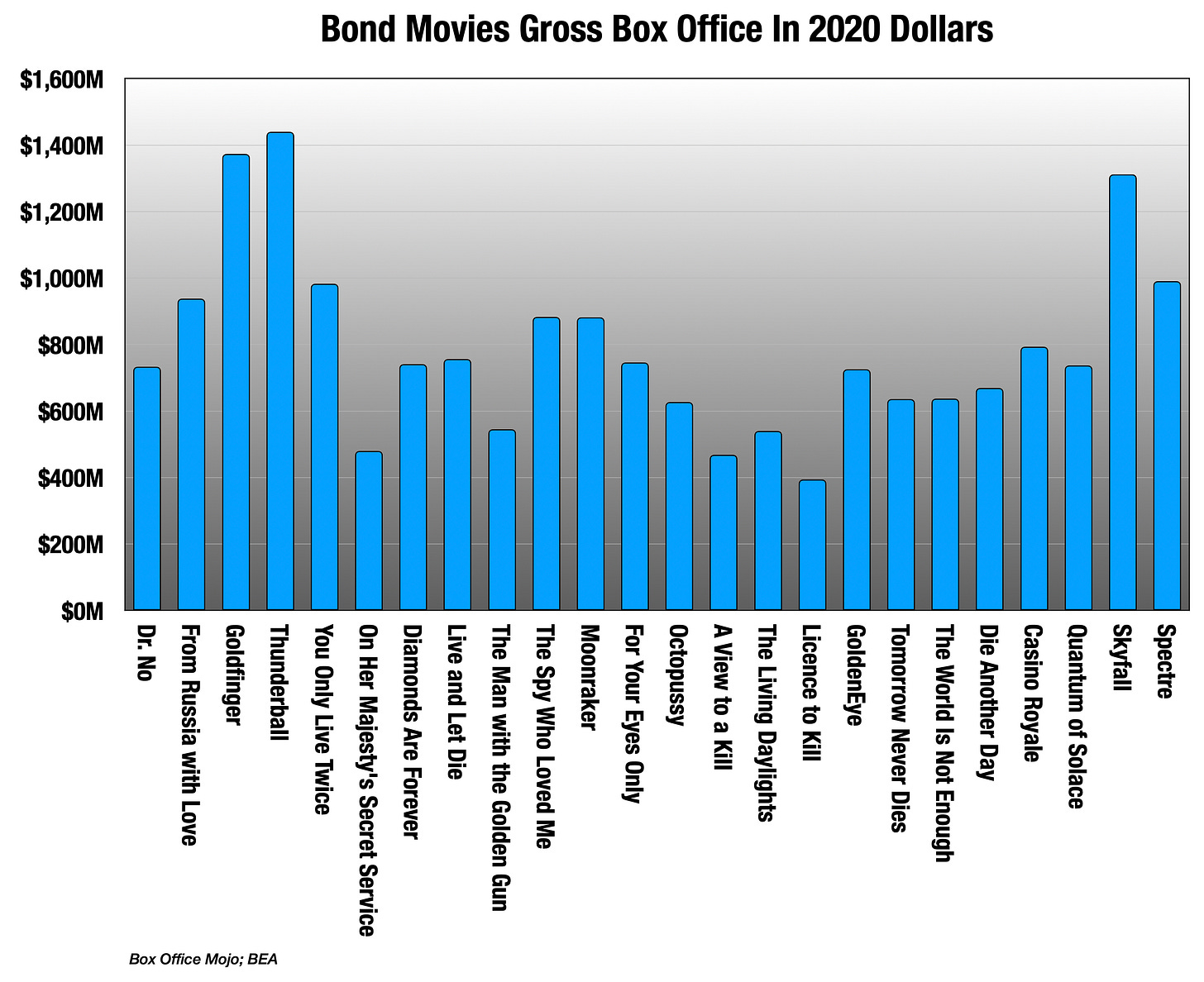

Bond is the most popular movie character of all time. Using the PCE movie theater deflator, Bond movies have grossed $19 billion in 2020 dollars. It is hardly Disney, who has the three most valuable cultural properties in the world — Marvel, Star Wars, and Pixar/Disney Animation — but it is a very good franchise, with the longest history.

The End?

Many non-media companies who have bought studios have tired of them quickly. It is a long list that includes Transamerica, Gulf+Western, and Matsushita, and now we can add AT&T. Amazon is here for the long haul, in my opinion, and so maybe this is the fourth and final chapter in this long, twisted history.